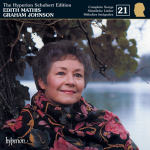

The Hyperion Schubert Edition, Vol. 21: Schubert in 1817 & 1818

2 吉他谱

0 求谱

0 拨片

The Hyperion Schubert Edition, Vol. 21: Schubert in 1817 & 1818专辑介绍

Recording details: October 1992

Rosslyn Hill Unitarian Chapel, Hampstead, London, United Kingdom

Produced by Martin Compton

Engineered by Tony Faulkner

Most of the discs issued so far in this series have programmes built around a theme, but some have been planned to show the chronology of the composer’s life and achievements. Volume 12, for example, features songs from 1811 to 1814; four discs (Volumes 7, 10, 20 and 22) concentrate on the huge and varied output of 1815; Volumes 17, 23 and 32 highlight the achievements of 1816. As the series progresses and draws to its close, each of the creative periods in Schubert’s life will be covered by a disc—in some cases a collaborative Schubertiad—which will depart from the idea of a thematic recital and return to the more conventional side of the programme builder’s art—a chronological corrective, perhaps, to the more wide-ranging and eclectic discs built around ideas, poets or themes. These two approaches to looking at (and listening to) the composer’s output are best taken in tandem.

1816 had been a watershed year, a period of change and conclusions. Towards its end Schubert seems to have accepted that his relationship with Therese Grob was over. He also stopped taking composition lessons with Antonio Salieri in December and gave up school-teaching himself (once and for all, he no doubt thought, but he was forced to return to the grindstone before long.) His move out of the parental home into the house of his friend Franz von Schober at the end of 1816 was a clear declaration of independence. These events are chronicled in more length and detail in the essay accompanying Volume 17. We now take up the thread of the story with a disc which features songs composed between January 1817 and December 1818, two of the most important years in the composer’s life, the first astonishingly productive, the next much less so. It would not be too much to say that this period represents the dawning of a new age in the Schubertian calendar, the progress from adolescence to maturity.

In terms of sheer numbers of songs the productivity of Schubert’s later years cannot compare with the earlier. No fewer than four discs are given over to 1815 (a year about which we have very little real biographical information) whereas well documented periods in the composer’s life are represented by a single disc in our series. It is also important to remember that the thematic recitals released earlier in the Schubert Edition have already made use of many of the great songs of the period. In order to obtain an accurate idea of the achievements of these years, the songs on this disc are to be considered side by side with others issued earlier in the series, not to mention the symphonic, operatic and chamber music which lies outside the scope of these recitals. The following list of the settings of 1817 will make clear the wide range of the composer’s literary interests in a year packed with musical activity of every kind. As in the work-list of The New Grove, Lieder are here listed in the chronology of the Deutsch catalogue although, as every Schubert scholar knows, much new information has come to light since Deutsch’s time. Following the confusion of a revised Mozart Köchel catalogue, musicologists have preferred not to assign new numbers to works, even if their dating is substantially different from Deutsch’s original thoughts. This means that in some cases the chronological order of the music (so far as we are able to establish it) is different from that suggested in the official catalogue.

The songs of 1817

D297: Augenlied [Volume 3] (Mayrhofer) early 1817(?)

D513A: Nur wer die Liebe kennt [Volume 21] (Werner) 1817(?)

D514: Die abgeblühte Linde [Volume 21] (Széchényi) 1817(?)

D515: Der Flug der Zeit [Volume 21] (Széchéyni) 1817(?)

D516: Sehnsucht [Volume 21] (Mayrhofer) Spring

D517: Der Schäfer und der Reiter [Volume 21] (Fouqué) April

D518: An den Tod [Volume 11] (Schubart) 1817

D519: Die Blumensprache [Volume 19] (Platner) October (?)

D520: Frohsinn [Volume 34] (Castelli) January

D521: Jagdlied [postlude to Die Nacht [Volume 6]] Werner January

D522: Die Liebe [Volume 21] (Leon) January

D523: Trost [Volume 21] (Unknown) January

D524: Der Alpenjäger [Volume 34] (Mayrhofer) January

D525: Wie Ulfru fischt [Volume 2] (Mayrhofer) January

D526: Fahrt zum Hades [Volume 2] (Mayrhofer) January

D527: Schlaflied [Volume 21] (Mayrhofer) January

D528: La pastorella al prato [Volume 9] (Goldoni) January

D530: An eine Quelle [Volume 21] (Claudius) February

D531: Der Tod und das Mädchen [Volume 11] (Claudius) February

D532: Das Lied vom Reifen [Volume 21] (Claudius) February

D533: Täglich zu singen [Volume 5] (Claudius) February

D534: Die Nacht [Volume 6] (Ossian) February

D536: Der Schiffer [Volume 2] (Mayrhofer) 1817(?)

D539: Am Strome [Volume 4] (Mayrhofer) March

D540: Philoktet [Volume 14] (Mayrhofer) March

D541: Memnon [Volume 14] (Mayrhofer) March

D542: Antigone und Oedip [Volume 14] (Mayrhofer) March

D543: Auf dem See [Volume 19] (Goethe) March

D544: Ganymed [Volume 5] (Goethe) March

D545: Der Jüngling und der Tod [Volume 3] (Spaun) March

D546: Trost im Liede [Volume 3] (Schober) March

D547: An die Musik [Volume 21] (Schober) March

D548: Orest auf Tauris [Volume 14] (Mayrhofer) March

D549: Mahomets Gesang [fragment] [Volume 24] (Goethe) March

D550: Die Forelle [Volume 21] (Schubart) early 1817

D551: Pax vobiscum [Volume 3] (Schober) April

D552: Hänflings Liebeswerbung [Volume 21] (Kind) April

D553: Auf der Donau [Volume 2] (Mayrhofer) April

D554: Uraniens Flucht [Volume 13] (Mayrhofer) April

D558: Liebhaber in allen Gestalten [Volume 21] (Goethe) May

D559: Schweizerlied [Volume 21] (Goethe) May

D560: Der Goldschmiedsgesell [Volume 24] (Goethe) May

D561: Nach einem Gewitter [Volume 19] (Mayrhofer) May

D562: Fischerlied [Volume 2] (Salis-Seewis) May

D563: Die Einsiedelei [Volume 34] (Salis-Seewis) May

D564: Gretchen im Zwinger [Volume 13] (Goethe) May

D565: Der Strom [Volume 2] (Unknown) June

D573: Iphigenia [Volume 3] (Mayrhofer) June

D577: Die Entzückung an Laura [Volume 16] (Schiller) August

D578: Abschied von einem Freunde [Volume 21] (Schubert) August

D579: Der Knabe in der Wiege [Volume 6] (Ottenwalt) September

D579A: Vollendung [Volume 11] (Matthisson) September–October

D579B: Die Erde [Volume 5] (Matthisson) September–October

D583: Gruppe aus dem Tartarus [Volume 14] (Schiller) September

D584: Elysium [Volume 11] (Schiller) September

D585: Atys [Volume 34] (Mayrhofer) September

D586: Erlafsee [Volume 21] (Mayrhofer) September

D587: An den Frühling [Volume 1] (Schiller) October

D588: Der Alpenjäger [Volume 1] (Schiller) October

D594: Der Kampf [Volume 34] (Schiller) November

D595: Thekla [Volume 9] second version (Schiller) November

D596: Lied eines Kindes [Volume 21] (Unknown) November

D637: Hoffnung [Volume 29] (Schiller) second version 1817(?)

D699: Der entsühnte Orest [Volume 14] (Mayrhofer) 1817(?)

D700: Freiwilliges Versinken [Volume 14] (Mayrhofer) 1817 (?)

This list provides a fascinating cross-section of the composer’s literary tastes as a young man. Goethe and Schiller, the Castor and Pollux of German literature, have seven settings each. Although this is no match for the wild enthusiasm of 1815 and 1816 when the composer seems to have been swept off his feet by their poems (and we in turn are swept off our feet by his response) some of the most important of the songs (Ganymed, Auf dem See, Gruppe aus dem Tartarus) were written in this year. There are four songs of Claudius, each one a gem, which all date from February, and show how Schubert would tarry with a poet in a concentrated burst of activity once he had alighted on something which chimed with his mood—in this case a revisiting of already familiar territory as well as a valediction. In the same month Schubert took his farewell of the poetry of Ossian, a young man’s enthusiasm if ever there was one: Die Nacht [Volume 6] is one of his last words in the realm of the ballad, and a magnificent testament to the composer’s hard-won Ossianic prowess. There are two settings of three other classic writers of an earlier age—Salis-Seewis, Matthisson and Schubart, each of them a favourite of earlier years and each graced by the composer with a final affectionate visit. An Italian setting of Goldoni (the enchanting La pastorella [Volume 9]) is the composer’s only other bow to the eighteenth century. The predominant concerns of 1817, as far as Schubert was concerned, were the present and the future—and that meant glorying in the musical and literary world of Vienna where almost all his friends were aspiring artists of one kind or another. From time to time Schubert set the words of Austrian writers of dubious literary credentials whose work he had come across in local almanacs: songs by Platner, Leon, Széchényi and Werner (the charismatic canon of St Stephen’s, Vienna) belong in this category. Settings by friends dear to Schubert were generally more inspired: poems by Anton Ottenwalt and Josef von Spaun were given enduring musical life in 1817. This respect for the creative efforts of his fellows was one of the reasns why the composer managed to gather around him a devoted following; he saw himself as an artistic primus inter pares rather than as an isolated Wunderkind, and this had ensured his popularity since his schooldays. Both of these songs (Der Knabe in der Wiege [Volume 6] and Der Jüngling und der Tod [Volume 3]) are one-off collaborations, created with audible affection and no doubt proudly received by the poets who little imagined that the scribblings of an hour would be their only passport to immortality. Franz von Schober (who was Schubert’s host for part of the year) was a more special friend and a more fluent poet, and it is not surprising that 1817 boasts three of the twelve Schober settings, one of them on this disc, An die Musik, universally accepted as the composer’s theme song, emblematic of Schubert’s attitude to his own art.

All of these collaborations with various local Viennese poets were put in the shade by Schubert’s enthusiasm in 1817 for the poetry of Johann Mayrhofer. There are no fewer than twenty Mayrhofer settings from this year, and there is no doubt that Schubert placed this poet in an entirely different category from that of his other young friends who dabbled in literature. This preference showed not only a respect and personal affection for the older poet, but the same sort of innate literary taste which would encourage Debussy and Poulenc to latch on respectively to Mallarmé and Apollinaire as prophets of a new age. Mayrhofer was a poet (Schlegel was another) who was a harbinger of the new Romanticism—the word which would lead music away from the paths of Beethoven and into excitingly uncharted territory. Schubert had met Mayrhofer as early as 1814, but in 1817 the friendship deepened considerably. We can hear this not only in the number of the poet’s texts which were set to music but more specifically in the composer’s new-found interest in the world of the classics and classical mythology. Mayrhofer wrote a number of poems which attempted to reinterpret classical themes in the light of his own tortured experience, but it is also certain that he turned the composer’s attention to poems by Goethe and Schiller preoccupied with the same themes. ‘Here is a real poet, with something new to teach me’, Schubert seems to be saying, and it is only relatively recently that song enthusiasts, long inclined wrongly to belittle Mayrhofer as a bungling neurotic, have come to agree with the composer’s judgement.

Another major step forward in 1817 was the advent of Johann Michael Vogl into the composer’s circle. In the absence of a good relationship with his father, Schubert seems to have responded well throughout his life to older men who decided to take the composer under their wing. Both Spaun and Mayrhofer (respectively nine and ten years older than Schubert) cast themselves in the role of protector and mentor; but earning the admiration of the singer Vogl, older than the composer, was a real turning point for Schubert. Since his student days he had admired Vogl at a distance in the Gluck operas. The vogue for Italian opera in Vienna (Schubert’s two overtures ‘in the Italian style’ date from this year, and were performed in 1818) meant that Vogl was at something of a loose end at the very time that Schubert needed an enthusiastic advocate for his songs—he could not after all continue to sing them himself in a thin voix de compositeur. Vogl was also exceptionally well read in the classics (and English) and in terms of his general cultivation and musical authority conformed to present-day ideas of what a Lieder singer should be. It is little wonder perhaps that it was his destiny to fashion the pattern of this unknown calling as he learned to adapt the cut of his vocal cloth to a brand-new medium.

Like many a superannuated star of the opera house, Vogl was a formidable grandee; he was also suspicious of association with so-called wonderful new talents. The first meeting between composer and singer (engineered by Spaun and Schober) was probably in March 1817. The singer haughtily sight-read through the first songs which came to hand (the first of which was Mayrhofer’s Augenlied, followed by Goethe’s Ganymed among others) and pronounced them ‘nicht übel’—the most patronising way possible of saying ‘quite nice’. The more he thought about it, however, the more convinced he became that Schubert was something special. Although he continued to underestimate the composer’s personal qualities, he was soon in awe of his genius. According to Mayrhofer’s recollections, Vogl ‘not only took care of Schubert materially, but in truth furthered him also spiritually and artistically’; he may be regarded as ‘his second father’. Vogl ascribed the gap between the intellectual and musical distinction he (incorrectly) perceived in Schubert to the fact that the young man composed in a trance-like state, as if unaware of what he was doing. In the manner of an accompanist humouring a diva, Schubert seems to have put up with this outrageous misconception the better to manage Vogl; one is reminded of how Claudius in Robert Graves’s novel about the Roman emperor ensures his survival by allowing people to think him a simpleton. Being patronised by Vogl was a small price to pay for having a charismatic interpreter. The classical interests of Mayrhofer were at one with those of Vogl; as a result composer and poet seem to have worked hard together to create Protean incarnations, in songs of re-interpreted myth, for the man who was once Vienna’s finest Orestes in Gluck’s Iphigenia. Despite the advent of other singers, younger of voice and more natural in demeanour, Vogl with his magisterial ‘foppishness’ (the criticism of some contemporaries) seems to have remained Schubert’s favourite singer. Although he had an essentially kindly nature, he remained a resolute snob, and a perpetual prey to parody from the younger men in the Schubert circle. Nevertheless, as the years went on, he was to play a continuing and vitally important part in the composer's day-to-day life.

Of the other achievements of 1817 mention must be made of a series of six Piano Sonatas written between March and August, the Sonata (or Duo) in A for violin and piano, and the Symphony No 6 in C which was begun in October. Other important events of the year were to do with a change in the circumstances of Schubert’s father. He was promoted to be head of a school in the Rossau suburb, which meant that the whole family moved from the house in the Säulengasse where the composer had written so much wonderful music. (The building today houses the Schubert Garage, its courtyard full of old cars waiting to be serviced.) At the beginning of 1817 Schubert was lodging at Franz von Schober’s apartment (it was there that he met Vogl for the first time). A crisis in the Schober family necessitated that Schubert should vacate these rooms and return to his father’s house—something which was almost certainly awkward and constricting after the freedom (and greater luxury) of the Schober lifestyle. The most comical entry for 1817 in the Documentary Biography is a letter to the publishers Breitkopf und Härtel from one Franz Schubert, ‘Royal Church Composer’ of Dresden. Schubert is a very common name (there are very many Franz Schuberts in the present-day Viennese phone-book). This namesake had been sent, in error, the returned manuscript of Erlkönig. Schubert of Dresden denounced this unsolicited mail as ‘trash’ and was outraged that someone had the temerity to misuse his name in this cheeky manner.

The songs of 1818

D607: Evangelium Johannis [Volume 21] (Bible) 1818

D611: Auf der Riesenkoppe [Volume 3] (Körner) March

D614: An den Mond in einer Herbstnacht [Volume 8] (Schreiber) April

D616: Grablied für die Mutter [Volume 21] (Unknown) June

D619: Singubüngen [Volume 34] (for two voices) (No text) July

D620: Einsamkeit [Volume 29] (Mayrhofer) July

D622: Der Blumenbrief [Volume 21] (Schreiber) August

D623: Das Marienbild [Volume 13] (Schreiber) August

D626: Blondel zu Marien [Volume 21] (Unknown) September

D627: Das Abendrot [Volume 34] (Schreiber) November

D628: Sonett I [Volume 27] (Petrarch trans. Schlegel) November

D629: Sonett II [Volume 27] (Petrarch trans. Schlegel) November

D630: Sonett III [Volume 27] (Petrarch trans. Gries) December

D631: Blanka (Das Mädchen) [Volumes 9, & 27] (Schlegel) December

D632: Vom Mitleiden Mariä [Volume 21] (Schlegel) December

This creative pattern differs strikingly from the fevered song work of 1817—although even that represented a large decrease in output since 1816. We might have the impression that Schubert is ‘winding down’ as a song composer and that he was turning his attention to opera, but the fact is that no opera was composed in 1818, and that it is a year of comparatively slim pickings in every medium. Of course there was some very great music composed; on the evidence of some of the pieces it is evident that Schubert was becoming a more concentrated artist than ever before. For example, he sets only one Mayrhofer text in 1818, but Einsamkeit is an enormous cantata and an attempt to create something new in song, a definite move towards the concept of a connected cycle of songs in the manner of Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte. Schubert wrote that it was ‘the best thing I have done’, referring perhaps to the work’s structural format. 1818 is the year of the poet Schreiber; all four of the settings date from that year, including the miraculous An den Mond in einem Herbstnacht [Volume 8] which is the composer’s earliest experiment in rondo form in song. Settings of the poet Schlegel towards the end of the year show the composer moving into a period where a probable connection between Friedrich Schlegel (resident in Vienna) and members of the Schubert circle was to stimulate the composer in new and challenging ways; he began to be interested in the philosophy of romanticism, and the ambitious and innovative songs of 1819 and 1820 reflect this. Volume 27 will be devoted to Schubert’s settings of the Schlegel brothers.

The smaller number of songs in this year might also suggest that Schubert was determined not to be typecast merely as a composer of songs. He was extremely ambitious in every form of music and worked hard in the early months of the year to complete the C major Symphony, No 6. It is possible that at this time he was asked to help out as a teacher at his father’s new school in the Rossau, and that he made an unwelcome return to teaching. This too may have played its part in restricting his output. There was the excitement of seeing his first song in print (Erlafsee, in an almanac) and of hearing one of his ‘Italian style’ overtures performed at the Theater an der Wien, but his application to join the Philharmonic Society as a practising member was unsuccessful. At the end of the year he was overjoyed to receive a commission to compose an opera, Die Zwillingsbrüder, for the Kärntnerthor Theatre. This was to be designed as a vehicle for Vogl’s return to the stage in a double starring role. It seems that both composer and singer were temporarily side-tracked into believing that their work together in Lieder was to be gloriously up-staged by ‘more important’ work in opera. A number of disappointments was in store for both of them in this regard.

In January 1818 the composer had set a quartet for SATB, Die Geselligkeit D609, with words by Johann Karl Unger, a professor of history and father of the famous mezzo Karoline. Unger was close friends with Prince Karl Esterházy who had a summer palace in Zseliz in Hungary and he effected an introduction (which amounted to a recommendation) between Schubert and this important noble family. Esterházy had two daughters, Countess Marie (b1802) and Countess Karoline (b1808), and the composer was duly appointed to be a music tutor for the little girls during the summer. Here was a chance to earn a little money and what better excuse than a summons from the nobility to leave the drudgery of teaching? In effect this meant a six-month stint away from his beloved home city. Schubert travelled to Zseliz sometime in May and only returned on 21 November with the rest of the Esterházy family. The Documentary Biography is rich in some of the very best letters that Schubert wrote ‘from exile’ to his family and friends. Although he missed Viennese life and members of his circle more keenly with each succeeding week, he enjoyed life in Hungary. ‘I am obliged to rely wholly on myself’, he wrote in September, not without a certain pride; a month earlier: ‘I live and compose like a god.’ While in Zseliz he composed the Deutsches Requiem (a work which he wrote for his brother Ferdinand to pass off as his own), as well as a series of piano duets no doubt written for the young countesses. The letters home are sometimes richly comic and show the strength of the composer’s relationships with his older brothers Ignaz and Ferdinand. Life ‘below stairs’ (and we must not forget that Schubert was billetted with the servants) seems to have been full of the lively intrigue and day-to-day scandal which is ever the staple diet of communities cut off from the big city, and dependent for entertainment on home-grown fun. In 1818 the countesses were perhaps too young for the composer’s romantic attentions (he was later to fall in love with Karoline) but a deliberately ambiguous letter to Schober and other friends (8 September) suggests that the very pretty chambermaid was often his companion (‘das Stubenmädchen sehr hübsch und oft meine Gesellschafterin’). It is quite possible that in Zseliz, far from his parents’ eyes, he discovered physical love with a woman for the first time, and this might have been one of those rare times in the composer’s life when the composition of music was upstaged by other equally pressing considerations.

Although Schubert met the baritone Karl von Schönstein (his exact contemporary who was later to play a large part in the performing history of Die schöne Müllerin) in Zseliz, the absence of a group of singers and poets at the summer castle certainly played a part in reducing the number of songs written in this period. As one scans the list above, one realises that for half of the year the composer was denied access to books. He no longer had the freedom of his friends’ libraries. It is likely that he had the Mayrhofer poem Einsamkeit in autograph, and that he had taken the volume of Schreiber poems with him to Zseliz (the singing exercises written for the young countesses were wordless). For six months it seems that he simply lacked the daily contact with literature coming out of other people’s pockets and into his own (the glorious German tradition of the Taschenbuch held sway amongst those who could not afford fine bindings) which had always inspired him to song. There is no better illustration than this of the huge part that city life, and city amenities, played in the composer’s inspiration. Schubert returned to Vienna starved of literature and intellectual companionship. He immediately took up residence with the poet Mayrhofer (no more Rossau schoolhouse for him!) and plunged into the Schlegel translations of Petrarch which were probably shown to him as soon as he had walked through Mayrhofer’s door. Petrarch and Schlegel were really poets to sink your teeth into. The 1818 sabbatical was over, and these settings were to lead to yet another new and adventurous phase in his composing life.

Graham Johnson © 1994

Franz Schubert: Schlaflied 'Schlummerlied' D527: Es mahnt der Wald, es ruft der Strom

Franz Schubert: Sehnsucht D516: Der Lerche wolkennahe Lieder

Franz Schubert: Die Liebe D522: Wo weht der Liebe hoher Geist?

Franz Schubert: Die Forelle D550: In einem Bächlein helle

Franz Schubert: Nur wer die Liebe kennt 'Impromptu' D513a

Franz Schubert: Der Flug der Zeit D515: Es floh die Zeit im Wirbelfluge

Franz Schubert: Trost D523: Nimmer lange weil' ich hier

Franz Schubert: Die abgeblühte Linde D514: Wirst du halten, was du schwurst

Franz Schubert: Das Lied vom Reifen D532: Seht meine lieben Bäume an

Franz Schubert: An eine Quelle D530: Du kleine grünumwachsne Quelle

Franz Schubert: An die Musik D547: Du holde Kunst, in wieviel grauen Stunden

Franz Schubert: Der Schäfer und der Reiter D517: Ein Schäfer sass im Grünen

Franz Schubert: Hänflings Liebeswerbung D552: Ahidi! ich liebe

Franz Schubert: Schweizerlied D559: Uf'm Bergli

Franz Schubert: Liebhaber in allen Gestalten D558: Ich wollt' ich wär' ein Fisch

Franz Schubert: Abschied von einem Freunde D578: Lebe wohl! Du lieber Freund!

Franz Schubert: Erlafsee D586: Mir ist so wohl, so weh'

Franz Schubert: Lied eines Kindes D596: Lauter Freude fühl' ich

Franz Schubert: Evangelium Johannes D607: In der Zeit sprach der Herr Jesus

Franz Schubert: Lob der Tränen D711: Laue Lüfte

Franz Schubert: Grablied für die Mutter D616: Hauche milder, Abendluft,

Franz Schubert: Der Blumenbrief D622: Euch Blümlein will ich senden

Franz Schubert: Blondel zu Marien D626: In düst'rer Nacht

Franz Schubert: Vom mitleiden Mariä D632: Als bei dem Kreuz Maria stand